“Why would I ever want to go to Sheol?”

There are questions that echo through the corridors of the soul, queries that pierce the veil between the temporal and the eternal, demanding not mere answers but profound reckonings. Why would I ever want to go to Sheol? What soul, in its deepest yearning for meaning and transcendence, sets its compass toward a silent grave—a place of shadow, detachment, and hollow waiting? If that is the promised “afterlife” of strict Yahwism, a realm of lingering gloom where the righteous and wicked alike descend into obscurity, then what magnet draws me there? When Ahura Mazda calls—not to dim subterranean courts, but to Paradise, to light, to renewal—why settle for darkness? So let the Pharisees be Pharisees: consign them to their laws, their rigid statutes, their lifeless rituals. We turn our gaze upward, toward the flame of Asha, toward the Father in Paradise. This essay unfolds this spiritual invitation, exploring the burdens of legalism, the shadows of ancient afterlives, and the radiant path of Zoroastrian wisdom, urging a turn from constraint to cosmic harmony. In an age where spiritual seekers grapple with inherited dogmas and yearn for authentic freedom, this reflection serves as a beacon, illuminating why the light of Ahura Mazda beckons over the dusk of Sheol.

To fully appreciate this call, we must delve into the historical and philosophical underpinnings that frame these contrasting visions. The Pharisees, as symbols of legalistic piety, and Sheol, as the shadowy abode of the dead in Hebrew tradition, represent a worldview rooted in meticulous observance and inevitable descent into oblivion. In contrast, Zoroastrianism offers a dynamic cosmology where moral agency leads to luminous eternity. This is not a dismissal of ancient faiths but a critique of systems that prioritize form over spirit, rule over renewal. As we expand this discourse, we will examine each facet in depth, drawing on exact scriptural insights, historical contexts, and philosophical reflections to reveal why the choice matters—not just for individuals, but for the collective human quest for truth.

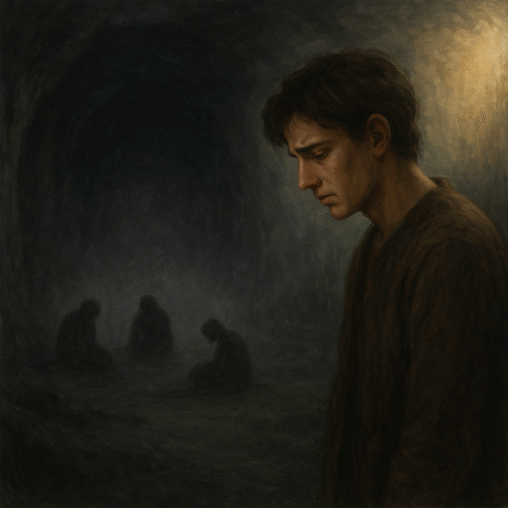

A Question in the Darkness

Why would I ever want to go to Sheol? This question is not born of whimsy but of existential urgency, a plea from the depths of the human spirit seeking purpose beyond the veil of mortality. In the Hebrew Bible, Sheol emerges as the underworld—a place of stillness, darkness, and inexorable death, where all souls, regardless of virtue or vice, converge in shadowy repose. It is not the fiery hell of later Christian imaginings nor the paradisiacal heaven, but a neutral, somber domain of silence and dust, often depicted as a subterranean pit far below the earth’s surface. The term “Sheol” appears 65 times in the Old Testament, evoking a land of forgetfulness where the dead are cut off from the living God, unable to praise or interact with the divine. As it is written exactly in Psalm 88:10-12 (King James Version): “Wilt thou shew wonders to the dead? shall the dead arise and praise thee? Selah. Shall thy lovingkindness be declared in the grave? or thy faithfulness in destruction? Shall thy wonders be known in the dark? and thy righteousness in the land of forgetfulness?” Here, Sheol (often paralleled with Abaddon) is a realm devoid of light, activity, and divine communion—a hollow waiting room for eternity.

This conception of the afterlife in early Judaism reflects a worldview where death is the great equalizer, stripping away earthly distinctions and consigning all to a muted existence. Unlike the vibrant afterlives of other ancient cultures, such as the Egyptian Duat with its judgments and rewards, Sheol offers no promise of joy or renewal. It is twilight without dawn, a place where the soul lingers in gloom, detached from the vibrancy of creation. As exactly stated in Ecclesiastes 9:10 (King James Version): “Whatsoever thy hand findeth to do, do it with thy might; for there is no work, nor device, nor knowledge, nor wisdom, in the grave, whither thou goest.” Why, then, would any soul aspire to such a fate? What allure lies in a destination that promises only absence and oblivion?

Contrast this with the luminous call of Ahura Mazda in Zoroastrianism, where the afterlife is not a descent into shadow but an ascent to Paradise—Garodman, the “House of Song,” a realm suffused with light, harmony, and the divine presence. Ahura Mazda, the Wise Lord, is the uncreated creator, embodying wisdom, benevolence, and the eternal struggle for good against chaos. In Zoroastrian cosmology, souls are judged at the Chinvat Bridge, where their deeds are weighed; the righteous cross into eternal bliss, while the wicked face purification or torment. Garodman is described exactly in the Avesta, Yasna 53.4 (translated by L. H. Mills): “The good shall part from the evil, the righteous from the wicked, and the just from the unjust; and all shall be in the light of the Good Mind.” This realm is a place of unending joy, where souls reunite with loved ones in the radiance of Ahura Mazda’s light, participating in the cosmic renewal known as Frashokereti—the final renovation where good triumphs utterly, as in Yasna 30.9 (Mills translation): “And when the punishment of the wicked shall come, then shall the good dominion be assigned to the righteous through the Good Mind, O Mazda.”

This stark dichotomy invites reflection: if Sheol represents the inexorable pull of gravity toward darkness, Garodman symbolizes the buoyant rise toward illumination. The question—”Why would I ever want to go to Sheol?”—challenges the resignation inherent in such a fate, urging seekers to envision an afterlife of purpose and presence. In Zoroastrianism, death is not an end but a transition, guided by Asha—the cosmic principle of truth and order that aligns human actions with divine will. Asha is not a burdensome law but a liberating force, encouraging good thoughts (humata), good words (hukhta), and good deeds (hvarshta) to forge a path to Paradise, as precisely articulated in Yasna 28.1 (Mills translation): “With outspread hands in petition for that help, O Mazda, first do I approach Thee, give me, O Thou Holy One, the strength of Thy Good Mind, through which to attain the wished-for prize of righteousness.”

Historically, these concepts intersect through Zoroastrian influence on Judaism during the Persian period, when Cyrus the Great liberated the Jews from Babylonian exile, exposing them to ideas of resurrection and dualism that later shaped apocalyptic visions in books like Daniel. As exactly in Daniel 12:2 (King James Version): “And many of them that sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life, and some to shame and everlasting contempt.” Yet, early Hebrew thought retained Sheol’s gloom, while Zoroastrianism offered hope. In a modern context, this question resonates with those disillusioned by rigid doctrines, seeking spiritual freedom beyond fear and formality. Let the Pharisees, emblematic of such rigidity, remain in their domain; we heed the call to light, where the soul finds not silence, but song.

As we ponder this darkness, it becomes clear that Sheol’s allure is none—it is a default, a resignation to fate without aspiration. The Hebrew Bible portrays it as deep underground, inaccessible and inescapable, a pit from which even kings and prophets cannot ascend. As in 1 Samuel 28:13-15 (King James Version): “And the king said unto her, Be not afraid: for what sawest thou? And the woman said unto Saul, I saw gods ascending out of the earth. And he said unto her, What form is he of? And she said, An old man cometh up; and he is covered with a mantle. And Saul perceived that it was Samuel, and he stooped with his face to the ground, and bowed himself. And Samuel said to Saul, Why hast thou disquieted me, to bring me up?” No wonders are worked there, no faithfulness declared; it is the land of forgetfulness, where God’s presence fades. Philosophically, this reflects an ancient worldview focused on earthly life, where the afterlife is secondary, a mere echo of existence. But for the seeker, this suffices not. Why embrace a theology that culminates in such desolation?

Ahura Mazda’s invitation, by contrast, is vibrant and participatory. The Gathas, Zoroaster’s hymns, invoke Ahura Mazda as the source of all good, calling humanity to co-create order against chaos. As exactly in Yasna 45.2 (Mills translation): “I will speak of the two Spirits, of whom the Holier thus spake to the Evil at the beginning of existence: Neither our thoughts, nor teachings, nor wills, nor beliefs, nor words, nor deeds, nor self-concepts, nor souls are the same.” Paradise is not earned through fear but through alignment with Asha, a principle that permeates existence. This spiritual dynamism offers liberation from the passive descent into Sheol, promising active engagement in eternal light. In times of global uncertainty, where conflicts like those in Gaza echo ancient struggles, this question urges us to choose paths of renewal over resignation, light over shadow.

Pharisaic Legalism: Law Over Spirit

The Pharisees, historically, represent a theological posture fixated on rule, ritual, and boundary—a stance that, while rooted in devotion, often elevates form above spirit, letter above heart. To let the Pharisees be Pharisees is to acknowledge this legacy without malice, recognizing it as a cautionary tale against the perils of legalism in any faith. In the context of first-century Judaism, the Pharisees were a sect dedicated to interpreting and applying the Torah to daily life, emphasizing oral traditions to “fence” the law and prevent violations. Their name, derived from Hebrew “perushim” meaning “separated ones,” reflects their commitment to purity and distinction from Hellenistic influences, making them guardians of Jewish identity during turbulent times. Yet, this zeal for law could devolve into legalism, where every act is weighed, every gesture accounted, transforming devotion into a prison rather than a vessel for the divine.

Observe how their system binds the spirit: the Pharisees expanded Mosaic laws with meticulous rules, such as prohibitions on healing on the Sabbath or elaborate hand-washing rituals, prioritizing external compliance over internal transformation. As exactly in Matthew 23:23-24 (King James Version): “Woe unto you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! for ye pay tithe of mint and anise and cummin, and have omitted the weightier matters of the law, judgment, mercy, and faith: these ought ye to have done, and not to leave the other undone. Ye blind guides, which strain at a gnat, and swallow a camel.” Here, legalism is exposed as a distortion, where minor observances eclipse major virtues. This critique is not unique to Christianity; it echoes broader religious concerns about legalism as a fear-based culture that complicates life and distances believers from grace.

Legalism, in essence, posits that spiritual standing depends on human effort—keeping commandments, traditions, or extra-biblical rules to earn divine favor. It fosters a performance-based faith, where anxiety over perfection replaces joy in relationship. In religious history, this manifests across traditions: from Pharisaic Judaism to Puritanical Christianity or rigid interpretations in Islam, where law becomes an idol, demoting the divine to a mere judge of technicalities. The problem lies not in laws themselves—which can guide ethical living—but in their elevation above spirit, leading to hypocrisy and burnout.

In contrast, Zoroastrianism sees moral life as an active alignment with Truth (Asha), not a checklist of prohibitions. Asha is the cosmic principle of righteousness, embodying the order Ahura Mazda established in creation. To obey Ahura Mazda is to participate in this luminous order, choosing good over evil through free will, without the burden of endless rules. As exactly in Yasna 31.1 (Mills translation): “To what land shall I flee? Whither to flee? From nobles and from my peers they sever me, nor are the people pleased with me, nor the Liar rulers of the land. How am I to please Thee, O Mazda Ahura?” The Gathas emphasize inner disposition: “Happy the man who is holy with perfect holiness,” focusing on intent rather than ritual precision. This liberates the spirit, allowing devotion to flow from love, not fear.

Let those who clutch at the old scrolls remain there—in their sepulchers of dusty rules. The Pharisees’ legacy, while contributing to Rabbinic Judaism’s richness, serves as a warning: when law overshadows spirit, faith stagnates. Modern critiques echo this, noting how legalism stifles spiritual freedom, leading to complex lives dominated by dos and don’ts. In Zoroastrianism, the path is simpler: align with Asha, combat Druj (falsehood), and advance toward Paradise. This contrast highlights why turning from legalism to light is essential—for it frees the soul to soar, unencumbered by chains of convention.

Expanding on Pharisaic practices, they developed the oral law to apply Torah to new contexts, such as Sabbath observance or dietary laws, aiming to sanctify daily life. Yet, this could lead to burdens, as seen in debates over carrying objects or harvesting on holy days. As exactly in Mark 7:3-4 (King James Version): “For the Pharisees, and all the Jews, except they wash their hands oft, eat not, holding the tradition of the elders. And when they come from the market, except they wash, they eat not. And many other things there be, which they have received to hold, as the washing of cups, and pots, brasen vessels, and of tables.” Similarly, in broader religion, legalism fosters judgmentalism, where adherents police others’ compliance, eroding community.

Zoroastrianism’s approach, influenced by Zoroaster’s reforms, rejects such rigidity. Ahura Mazda is not a distant judge but a benevolent creator inviting partnership. The Amesha Spentas (holy immortals) embody attributes like good mind and devotion, guiding adherents without oppressive mandates. As exactly in Yasna 45.4 (Mills translation): “Yes, I shall swear to be Thy priest, O Mazda, and to strive against the evil, and to be powerful in my support of Thy law.” This spiritual freedom contrasts sharply with legalism’s constraints, offering a model for contemporary seekers weary of doctrinal heaviness.

In today’s world, where religious extremism often revives legalistic tendencies, this section underscores the need for balance. Legalism sucks the joy from faith, as one critic notes, turning it into a grind rather than a grace-filled journey. By letting the Pharisees be Pharisees, we honor their historical role while choosing a path of liberation, walking unshackled toward the fire of Asha.

The Shadows of Sheol

In Hebrew and later Yahwistic lore, Sheol is a place neither bright nor warm: a land of silence, dust, forgetfulness, and absence. It is twilight without dawn. What solace is in that? What joy? What purpose? To explore Sheol is to confront the starkness of early biblical afterlife concepts, where death strips away vitality, leaving souls in a muted limbo. Described as the “realm of the dead,” Sheol is underground, a pit or grave extended to encompass all departed, righteous and wicked alike. As exactly in Job 10:21-22 (King James Version): “Before I go whence I shall not return, even to the land of darkness and the shadow of death; A land of darkness, as darkness itself; and of the shadow of death, without any order, and where the light is as darkness.” No activity, no praise, no divine interaction—only endless quiet.

This view evolved from ancient Near Eastern ideas, where the underworld was a common motif, but in Hebrew thought, it emphasized life’s preciousness over posthumous reward. As exactly in Psalm 6:5 (King James Version): “For in death there is no remembrance of thee: in the grave who shall give thee thanks?” Even kings like Hezekiah lament descending to Sheol, cut off from the living, as in Isaiah 38:18 (King James Version): “For the grave cannot praise thee, death can not celebrate thee: they that go down into the pit cannot hope for thy truth.”

Unlike later developments in Judaism influenced by Zoroastrianism—such as resurrection in Daniel—early Sheol offers no hope of revival, only perpetual gloom. As exactly in Daniel 12:2 (King James Version): “And many of them that sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life, and some to shame and everlasting contempt.”

Meanwhile, Zoroastrian cosmology offers something else: a Garōdmān (Paradise) suffused with light, song, and the presence of Ahura Mazda. After judgment, righteous souls enter this realm of bliss, where they enjoy eternal communion with the divine, free from suffering. The Avesta describes it as the “best existence,” a place of unending happiness and harmony, as in Yasna 53.4 (Mills translation): “The good shall part from the evil, the righteous from the wicked, and the just from the unjust; and all shall be in the light of the Good Mind.”

If ever one must choose between Sheol’s hollow silence or Paradise’s song, let the answer be clear. Sheol’s shadows symbolize a theology focused on earthly obedience without eternal vibrancy, while Garodman invites active moral engagement leading to luminous reward. This contrast highlights why turning to Ahura Mazda’s light is compelling—it promises purpose beyond the grave.

Expanding, Sheol’s depictions vary: sometimes a prison, as in Psalm 107:10 (King James Version): “Such as sit in darkness and in the shadow of death, being bound in affliction and iron;” sometimes a gathering place, as in Genesis 37:35 (King James Version): “And all his sons and all his daughters rose up to comfort him; but he refused to be comforted; and he said, For I will go down into the grave unto my son mourning. Thus his father wept for him.” But consistently, it is devoid of light and life. In Zoroastrianism, the afterlife is dualistic: Heaven for good, Hell for evil, with eventual purification, as in Yasna 30.9 (Mills translation): “And when the punishment of the wicked shall come, then shall the good dominion be assigned to the righteous through the Good Mind, O Mazda.”

Philosophically, Sheol’s gloom reflects a pre-eschatological worldview, while Zoroastrian Paradise offers hope, making it a superior spiritual destination for those seeking joy over desolation.

Yahweh’s Shadows vs. Ahura Mazda’s Daylight

The path of Yahwistic tradition often carries with it shadows: law without mercy, letter without spirit, fear over trust. When the divine is reduced to a judge of technicalities, faith loses its wings. This critique focuses on legalistic interpretations, not the essence of Yahweh’s covenant, which emphasizes justice and compassion. Yet, in strict adherence, shadows emerge—fear-driven submission rather than heartfelt partnership, as in Isaiah 45:7 (King James Version): “I form the light, and create darkness: I make peace, and create evil: I the Lord do all these things.”

But following Ahura Mazda is not fear-driven submission—it’s a courageous ascent, a partnership with creation, a walk in light. Ahura Mazda, as supreme creator, invites humanity to combat chaos through Asha, fostering growth and renewal, as in Yasna 44.3 (Mills translation): “This I ask Thee, tell me truly, O Ahura: Who is the Creator, the first Father of Righteousness? Who established the path of the sun and the stars? Who but Thou is it through whom the moon waxes and wanes?”

Zoroastrianism’s influence on Judaism is evident in dualism and afterlife concepts, where light triumphs over darkness. In the Old Testament, passages like Isaiah 45:7 echo this, but early Yahwism retained Sheol’s shadows.

Christianity and Islam further absorbed these: New Testament light motifs, as in John 1:5 (King James Version): “And the light shineth in darkness; and the darkness comprehended it not.” And Quranic light verses, as in Surah An-Nur 24:35 (Yusuf Ali translation): “Allah is the Light of the heavens and the earth. The Parable of His Light is as if there were a Niche and within it a Lamp: the Lamp enclosed in Glass: the glass as it were a brilliant star: Lit from a blessed Tree, an Olive, neither of the east nor of the west, whose oil is well-nigh luminous, though fire scarce touched it: Light upon Light! Allah doth guide whom He will to His Light: Allah doth set forth Parables for men: and Allah doth know all things.”

We do not move toward rules; we move toward Truth, Light, and Eternity. This shift from shadows to daylight liberates the spirit, aligning with universal calls for moral freedom.

A Call to Choice

So—hear me now: Let the Pharisees be Pharisees. Set them in their traditional seats; let them chant their legal tomes. We will turn elsewhere. We will ask: Why aim for Sheol, whose doors are sealed in cold silence? Why idolize a god who demands ritual over heart, law over growth?

Instead, we choose Ahura Mazda: the Father in Paradise, the source of radiant order, the guide of souls toward ultimate Light. This call echoes shared spiritual heritage—Zoroastrian dualism influencing biblical choices, as in Deuteronomy 30:19 (King James Version): “I call heaven and earth to record this day against you, that I have set before you life and death, blessing and cursing: therefore choose life, that both thou and thy seed may live.” And Quranic guidance to light, as in Surah Al-Baqarah 2:257 (Yusuf Ali translation): “Allah is the Protecting Friend of those who believe. He bringeth them out of darkness into light. As for those who disbelieve, their patrons are false deities. They bring them out of light into darkness. Such are rightful owners of the Fire. They will abide therein.”

In choosing Asha, we embrace freedom, participating in cosmic renewal. Let legalism fade; the light awaits.