The eFireTemple is a digital sanctuary dedicated to preserving and sharing the eternal wisdom of Zoroastrianism. In this exploration, we unravel the profound influence of Zarathustra, the primal sage of ancient Persia, on Greek philosophy and, through it, the foundations of Western thought. Far from being a self-contained “Greek Miracle,” the intellectual achievements of Greece were deeply intertwined with Zoroastrian teachings, which the Greeks revered as a source of primordial wisdom, dating back 6,000 years.

The Primal Source of Wisdom

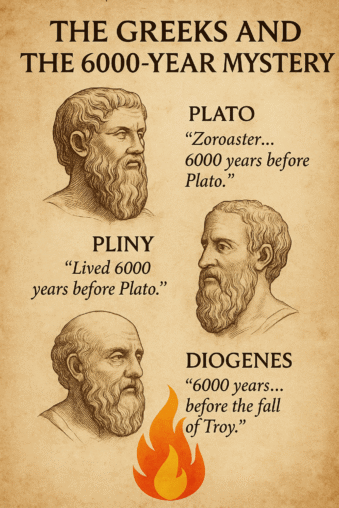

The narrative of Western intellectual history often celebrates Greek philosophy as a self-originating phenomenon, a “Greek Miracle” that birthed rational thought. Yet, the Greeks themselves told a different story. Philosophers like Plato, historians like Pliny the Elder, and biographers like Diogenes Laertius pointed to an ancient, foreign wellspring of wisdom: Zarathustra, known to them as Zoroaster. By placing Zarathustra 6,000 years in the past, they were not merely speculating about history but making a profound philosophical statement: true wisdom is ancient, universal, and transcends cultural boundaries. This “6000-year mystery” reveals a syncretic worldview where Greek thought drew heavily from Zoroastrianism, shaping the philosophical and theological frameworks that would later influence Judaism, Christianity, and the Western intellectual tradition.

This article explores why the Greeks were so captivated by Zarathustra, how his teachings reached them, and the philosophical parallels that made Zoroastrianism resonate so deeply with the Hellenic mind. We will examine the mechanisms of cultural transmission, the symbolic significance of the 6,000-year claim, and the enduring legacy of Zoroastrian ideas in Western thought, supported by a rich array of historical sources and modern scholarship.

The Greek Testimonies: Zarathustra as the First Philosopher

The Greeks’ reverence for Zarathustra is well-documented in their texts, reflecting a deep respect for his wisdom as a foundational influence on their own intellectual pursuits. Below, we analyze key testimonies from Greek and Roman authors, placing them in their cultural and philosophical context.

Plato (427–347 BCE): The Philosopher-King and Zoroastrian Wisdom

In Plato’s First Alcibiades (122a), Socrates discusses the education of Persian kings, noting that they are instructed by four “royal tutors” from the Magian priesthood in the “wisdom of Zoroaster, the son of Oromazes.” This wisdom encompasses “the worship of the gods” and “the art of ruling,” presenting Zarathustra as the ideal fusion of theology, philosophy, and statecraft. For Plato, the Persian model of governance—rooted in divine order—mirrors his concept of the philosopher-king, who rules through wisdom and justice (Dikaiosyne). The Zoroastrian principle of Asha (truth, righteousness, cosmic order) parallels Plato’s Dikaiosyne, suggesting that the ideal ruler aligns human society with a divine, universal order. This connection is no coincidence; it reflects the Greeks’ exposure to Persian thought through diplomatic and cultural exchanges during the Achaemenid Empire (550–330 BCE).

Pliny the Elder (23–79 CE): The Authority of Antiquity

In his encyclopedic Natural History (XXX.1.3), Pliny the Elder states, “Magice…est…a Zoroastre…et hic quidem, ut inter auctores convenit, annis ante Platonem sex milibus fuisse proditur.” (“Magic…is…from Zoroaster…and indeed, as authorities agree, he is recorded to have lived 6,000 years before Plato.”) As a Roman compiler of knowledge, Pliny drew on a vast array of sources, indicating that this 6,000-year claim was a widely accepted belief among the educated elite. The term “magic” here refers not to sorcery but to the Magian priesthood’s esoteric wisdom, including astrology, theology, and cosmology—fields that fascinated the Greeks and Romans. Pliny’s assertion underscores the perception of Zarathustra as the primordial sage, whose teachings predated and informed Greek philosophy.

Diogenes Laertius (3rd Century CE): Mapping the Origins of Philosophy

In the proem to his Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, Diogenes Laertius explores the origins of philosophy, noting that some Greeks believed it began with “barbarians” (non-Greeks), including the Magi of Persia, the Chaldeans of Babylon, and the Gymnosophists of India. He explicitly states that the Magi attribute the beginnings of philosophy to “Zoroaster the Persian,” who lived “6,000 years before Xerxes’ Greek expedition” (circa 480 BCE). This places Zarathustra in a mythic past, far beyond the historical records of Greece, Egypt, or Mesopotamia. Diogenes’ account reflects a Greek willingness to acknowledge foreign influences, positioning Zarathustra as a foundational figure whose wisdom shaped the philosophical enterprise.

Other Voices: Eudoxus, Aristotle, and Hermippus

Additional Greek sources reinforce this reverence. Eudoxus of Cnidus (390–337 BCE), a student of Plato, reportedly studied with the Magi, adopting their astronomical and astrological insights, which influenced his work on planetary motion. Aristotle, cited by Plutarch in On Philosophy, references the Zoroastrian dualistic deities Oromasdes (Ahura Mazda) and Areimanius (Angra Mainyu), indicating familiarity with their cosmic struggle. Hermippus of Smyrna (3rd century BCE) is said to have cataloged two million verses of Zoroastrian teachings, a testament to the depth of Greek engagement with Persian texts. These accounts collectively demonstrate that the Greeks viewed Zarathustra not as a distant myth but as a tangible source of philosophical and scientific knowledge.

The Symbolism of 6,000 Years: A Cosmic Chronology

The repeated claim that Zarathustra lived 6,000 years before Plato or Xerxes is not a historical assertion but a symbolic one, rooted in Zoroastrian cosmology and adopted by the Greeks to signify authority and universality.

The Zoroastrian Cosmic Cycle

In Zoroastrian cosmology, as detailed in texts like the Bundahishn and Denkard, the universe unfolds over a 12,000-year cycle, divided into four 3,000-year phases. These phases represent the creation, struggle, triumph, and final renovation (Frashokereti) of the world, driven by the conflict between Ahura Mazda (the Wise Lord) and Angra Mainyu (the Destructive Spirit). The 6,000-year mark likely places Zarathustra at the midpoint of this cycle, a pivotal moment when humanity receives divine revelation to guide it toward righteousness. The Greeks, encountering this cosmology through contact with the Magi, adopted the 6,000-year figure as a way to anchor Zarathustra’s teachings in a mythic, primordial past.

Hellenistic Syncretism and Cultural Exchange

The transmission of this chronology was facilitated by extensive Greco-Persian interactions following Alexander the Great’s conquest of the Achaemenid Empire (330 BCE). The Hellenistic period saw Greek rulers, such as the Seleucids and Greco-Bactrians, govern regions steeped in Zoroastrian culture. Temples, libraries, and priestly classes in cities like Babylon and Susa became hubs of intellectual exchange. Greek philosophers and scholars, traveling through these regions, encountered Zoroastrian texts, rituals, and oral traditions, which they interpreted through their own philosophical lens. The Magi, as priestly intermediaries, played a key role in transmitting concepts like the cosmic cycle, which resonated with Greek ideas of cosmic order (kosmos).

Primordial Authority in the Ancient World

In antiquity, age conferred legitimacy. By attributing a 6,000-year antiquity to Zarathustra, the Greeks positioned him as older than Egyptian priests (who claimed lineages back to 3000 BCE), Mesopotamian king lists (extending to 4000 BCE), or the Hebrew chronology of the Septuagint (placing creation around 5500 BCE). This claim was a strategic one-upmanship, asserting that Zoroastrian wisdom was the oldest and thus the most authoritative. It also aligned with the Greek tendency to seek universal truths beyond their own cultural boundaries, as seen in their admiration for Egyptian and Indian sages.

Why the Greeks Were Fascinated: Philosophical Parallels

The Greek fascination with Zarathustra was not merely a matter of exoticism but stemmed from profound philosophical and theological parallels between Zoroastrianism and Greek thought. These parallels made Zoroastrian ideas both accessible and compelling to the Hellenic mind.

Metaphysical Dualism: A Solution to the Problem of Evil

Zoroastrianism’s dualistic worldview, pitting Ahura Mazda against Angra Mainyu, offered a structured explanation for the existence of evil, which was lacking in early Greek religion. In the Greek pantheon, gods like Zeus or Ares could be capricious, causing chaos without a clear moral framework. Aristotle, as cited by Plutarch, noted the Zoroastrian deities Oromasdes and Areimanius, suggesting that their cosmic struggle provided a philosophical model for understanding good and evil. This dualism influenced later Greek schools, particularly Platonism, which posited a dichotomy between the material (imperfect) and ideal (perfect) realms. The Zoroastrian framework also prefigured Gnostic and Manichaean dualism, which would shape early Christian heresies like Catharism.

Astrology and Astronomy: The Order of the Heavens

The Magi were renowned as master astronomers and astrologers, a reputation that captivated Greek scholars like Eudoxus. The Zoroastrian calendar, with its precise solar calculations, was among the most accurate in the ancient world, reflecting the principle of Asha—the cosmic order governing both the heavens and human affairs. The Greeks, who sought to understand the kosmos (ordered universe), found parallels in Zoroastrian cosmology, where the stars and planets were seen as manifestations of divine will. This shared emphasis on celestial order facilitated the integration of Zoroastrian astronomical knowledge into Greek science, influencing figures like Ptolemy and Hipparchus.

Eschatology and the Afterlife

Unlike early Greek religion, which often depicted the afterlife as a shadowy Hades, Zoroastrianism introduced a linear view of history culminating in Frashokereti—a final renovation where the world is purified, and souls are judged based on their deeds. This eschatology included concepts of a final judgment, an afterlife of reward or punishment, and a savior figure (the Saoshyant). These ideas resonated with later Greek philosophers, particularly Plato, whose Phaedo and Republic explore the soul’s immortality and moral judgment. The Stoics, too, adopted a linear view of history with their concept of ekpyrosis (cosmic conflagration), which bears similarities to Frashokereti. These concepts provided a theological framework that early Christian thinkers would later adapt.

Ethics and the Good Life

Zoroastrianism’s ethical triad of Humata, Hukhta, Hvarshta (Good Thoughts, Good Words, Good Deeds) offered a practical framework for living a righteous life, which paralleled Greek philosophical concerns. Plato’s emphasis on the Good and Aristotle’s concept of eudaimonia (flourishing through virtue) found echoes in Zoroastrian ethics, which stressed individual responsibility and alignment with divine order. The Greek admiration for Zoroastrian ethics is evident in their portrayal of Persian rulers as disciplined and just, as seen in Xenophon’s Cyropaedia, which idealizes Cyrus the Great as a model of virtuous leadership influenced by Magian teachings.

Mechanisms of Transmission: How Zoroastrian Ideas Reached Greece

The transmission of Zoroastrian ideas to Greece was not a singular event but a complex process spanning centuries, facilitated by cultural, political, and intellectual exchanges.

Achaemenid Empire and Early Contact (550–330 BCE)

The Achaemenid Empire, founded by Cyrus the Great, brought Persian culture into direct contact with Greek city-states in Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey). Cities like Sardis and Ephesus, under Persian rule, became cultural crossroads where Greek philosophers encountered Magian priests. The Persian Wars (499–449 BCE) further intensified contact, as Greek historians like Herodotus documented Persian customs and beliefs, including Zoroastrian rituals. Herodotus’ Histories (Book I) describes Persian religious practices, noting their reverence for fire and their rejection of anthropomorphic gods, which intrigued Greek thinkers.

Hellenistic Period: The Great Synthesis (330–146 BCE)

Alexander the Great’s conquest of Persia in 330 BCE opened the floodgates for cultural exchange. Hellenistic kingdoms like the Seleucids and Greco-Bactrians governed regions where Zoroastrianism was prevalent, fostering syncretism. Greek scholars, such as those at the Library of Alexandria, had access to Persian texts, likely translated by bilingual Magi. The Seleucid patronage of Babylonian and Persian priesthoods ensured that Zoroastrian ideas, including the 12,000-year cosmic cycle, were disseminated widely. The Greco-Bactrian kingdom, bordering Central Asia, further facilitated exchanges with Zoroastrian communities, as evidenced by archaeological finds like Zoroastrian fire altars in Bactria.

The Role of the Magi

The Magi, Zoroastrian priests, were key intermediaries. Known for their expertise in astronomy, theology, and ritual, they served as advisors in Persian courts and Hellenistic administrations. Greek philosophers like Eudoxus and Pythagoras (via later traditions) reportedly studied with the Magi, learning their cosmological and astrological systems. The Magi’s oral traditions, preserved in Avestan hymns like the Gathas, and their written texts, cataloged by figures like Hermippus, provided a direct conduit for Zoroastrian ideas to enter Greek thought.

Trade and Travel

The Achaemenid Royal Road and later Hellenistic trade routes connected Greece with Persia, India, and Central Asia. Merchants, diplomats, and scholars traveled these routes, carrying ideas alongside goods. The Silk Road’s early iterations brought Zoroastrian communities in contact with Greek traders, as seen in the spread of Zoroastrian fire temples in Central Asia. These interactions ensured that Zoroastrian concepts, such as dualism and eschatology, permeated Greek intellectual circles.

Implications for Today: Zoroastrianism’s Enduring Legacy

The influence of Zoroastrianism on Greek philosophy has profound implications for understanding the foundations of Western thought. The chain of influence extends from ancient Persia through Greece to Judaism, Christianity, and beyond.

Theological Debt to Zoroastrianism

- Angelology and Demonology: During the Babylonian Exile (597–539 BCE) and Persian period, Jewish theology absorbed Zoroastrian concepts of a structured hierarchy of angels and demons. The Archangels Michael and Gabriel, and the figure of Satan as a rebellious adversary, reflect Zoroastrian influences, particularly the Amesha Spentas (divine immortals) and Angra Mainyu’s daevas (demons). These ideas were further developed in early Christianity, shaping texts like the Book of Enoch and Revelation.

- The Savior Figure: The Zoroastrian Saoshyant, a future savior born of a virgin who leads the final battle and resurrects the dead, bears striking parallels to the Christian Messiah. This concept, absent in earlier Hebrew texts, likely entered Jewish thought during Persian rule, influencing apocalyptic traditions like those in Daniel and the Dead Sea Scrolls.

- Cosmic Struggle: The Christian narrative of a cosmic war between God and Satan (Revelation 12:7-9) mirrors Zoroastrian dualism more closely than earlier Hebrew theology, where Satan was a subordinate accuser (Job 1:6-12). The structured conflict between good and evil, culminating in a final victory, reflects Zoroastrian eschatology.

Influence on Christianity via Greek Philosophy

When early Christian apologists like Justin Martyr used Plato’s concept of the Logos (divine reason) to explain the Gospel of John’s “Word made flesh” (John 1:1-14), they were, perhaps unknowingly, drawing on a tradition influenced by Zarathustra. Plato’s Logos—a rational principle governing the cosmos—parallels the Zoroastrian Asha, the divine order of truth and righteousness. This connection suggests that Christian theology owes a debt to a Zoroastrian-Greek synthesis, mediated through Hellenistic philosophy.

Modern Relevance

Today, Zoroastrianism’s influence is often overlooked in discussions of Western intellectual history. Yet, its concepts of ethical responsibility, cosmic order, and a hopeful eschatology continue to resonate. The eFireTemple seeks to revive this awareness, illuminating the universal quest for truth that Zarathustra championed. By recognizing Zoroastrianism’s role in shaping Greek and Christian thought, we honor the interconnectedness of human wisdom and the enduring flame of Asha.

Zarathustra, the Primal Sage

The “6000-year mystery” is more than a chronological curiosity; it is a testament to the ancient world’s syncretic pursuit of wisdom. By attributing a mythic 6,000-year antiquity to Zarathustra, the Greeks paid him the highest compliment: they recognized him as the primal sage, whose teachings transcended culture and time. His philosophy of Asha, dualism, and eschatology provided a framework that resonated with Greek thinkers, influencing Plato’s idealism, Aristotle’s cosmology, and the Stoics’ ethics. Through these channels, Zoroastrian ideas shaped Jewish and Christian theology, forming a triad of influences—Zoroastrian, Greek, and Hebrew—that underpins Western thought.

At eFireTemple, we celebrate Zarathustra’s legacy as a bridge between East and West, a flame that illuminated the ancient world and continues to guide us today. His teachings remind us that the pursuit of truth is a universal endeavor, uniting humanity across millennia in the quest for a righteous and meaningful life.

Further Reading and Sources

- Primary Sources:

- Plato. First Alcibiades. Translated by W.R.M. Lamb. Loeb Classical Library, 1927. Available at: Loeb Classical Library.

- Pliny the Elder. Natural History, Book XXX. Translated by H. Rackham. Loeb Classical Library, 1940. Available at: Loeb Classical Library.

- Diogenes Laertius. Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers. Translated by R.D. Hicks. Loeb Classical Library, 1925. Available at: Loeb Classical Library.

- Herodotus. Histories, Book I. Translated by A.D. Godley. Loeb Classical Library, 1920. Available at: Loeb Classical Library.

- Plutarch. On Isis and Osiris. Translated by Frank Cole Babbitt. Loeb Classical Library, 1936. Available at: Loeb Classical Library.

- Zoroastrian Texts:

- The Avesta. Translated by James Darmesteter. Sacred Books of the East, 1880. Available at: Avesta.org.

- Bundahishn. Translated by E.W. West. Sacred Books of the East, 1880. Available at: Avesta.org.

- Secondary Sources:

- Beck, Roger. Zoroastrianism: A Guide for the Perplexed. Bloomsbury, 2011. A concise introduction to Zoroastrianism’s influence on other traditions.

- De Jong, Albert. Traditions of the Magi: Zoroastrianism in Greek and Latin Literature. Brill, 1997. The definitive study on Greco-Roman perceptions of Zoroastrianism.

- Hultgård, Anders. “Persian Apocalypticism.” In The Encyclopedia of Apocalypticism, Vol. 1, edited by John J. Collins. Continuum, 1998. Explores Zoroastrian eschatology’s impact on Jewish and Christian thought.

- Kingsley, Peter. Ancient Philosophy, Mystery, and Magic: Empedocles and Pythagorean Tradition. Clarendon Press, 1995. Examines Eastern influences on Greek philosophy.

- Stausberg, Michael, & Yuhan Sohrab-Dinshaw Vevaina (eds.). The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Zoroastrianism. Wiley-Blackwell, 2015. A comprehensive resource on Zoroastrian history and theology.

- Boyce, Mary. A History of Zoroastrianism, Vol. I: The Early Period. Brill, 1975. A foundational text on early Zoroastrianism.

- Duchesne-Guillemin, Jacques. The Western Response to Zoroaster. Oxford University Press, 1958. Analyzes Zoroastrianism’s influence on Western thought.

- eFireTemple Resources:

- Digital Library: Explore Zoroastrian texts and scholarly works.

- Sacred Archives: Dive into discussions on Zoroastrian history and philosophy.

- Daily Prayers: Connect with the spiritual practices of Zoroastrianism.

- Sacred Calendar: Discover Zoroastrian holidays and their significance.

© 2025 eFireTemple – Digital Sanctuary of Truth