“Empires are not only roads and walls; they are the highways of thought and spirit.” — Inspired by the legacy of Cyrus the Great, whose empire bridged civilizations.

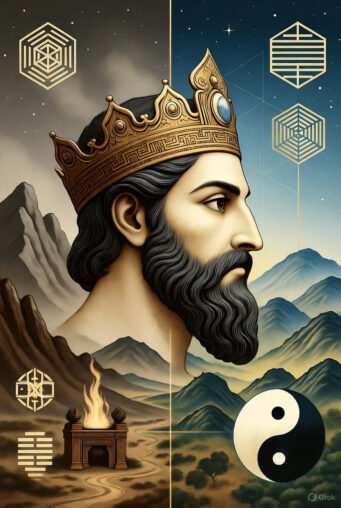

Persia at the Crossroads of Human Consciousness

The Axial Age (c. 800–300 BCE), a term coined by philosopher Karl Jaspers in The Origin and Goal of History (1953), marks a pivotal era in human intellectual and spiritual evolution. During this time, civilizations across Eurasia developed profound insights into ethics, universal order, and human purpose. From the ethical monotheism of Hebrew prophets to the introspective philosophies of Indian sages like the Buddha and Mahavira, the rational inquiries of Greek thinkers such as Socrates and Plato, and the harmonious cosmologies of Chinese mystics like Lao Tzu and Confucius, humanity awakened to transcendent truths that shaped modern thought.

However, these awakenings were interconnected through the Achaemenid Persian Empire, founded by Cyrus the Great (c. 600–530 BCE). As the first true superpower spanning from the Mediterranean to the Indus Valley, Persia served as the central conduit for cultural, philosophical, and spiritual exchange. Through its vast networks of roads, tolerant policies, and mobile priesthood, Persia disseminated Zoroastrian cosmology—centered on Asha (divine truth, order, and righteousness)—to distant lands, influencing emerging traditions in India, Central Asia, and China.

This article delves into the historical, archaeological, political, and cultural mechanisms by which Persia transmitted Zoroastrian ethical dualism, cosmic harmony, and divinatory practices eastward. We explore how Asha, the moral backbone of Zoroastrianism revealed by the prophet Zarathustra (Zoroaster) around 1500–1200 BCE, resonated with and enriched the Dao (Tao)—the eternal Way of Chinese philosophy—and the I Ching’s cyclical wisdom. Drawing on archaeological discoveries, scholarly analyses, and textual evidence, we affirm Zoroastrianism’s foundational role in fostering a morally infused global consciousness, positioning Persia not merely as a geographic bridge but as the spiritual axis of the Axial Age.

The Achaemenid Empire: Highways of Thought

1. The Scope of Cyrus’ Vision

Cyrus the Great’s conquests created the largest empire the world had seen, but his true innovation lay in governance. Unlike the Assyrians or Babylonians, who imposed cultural uniformity through force, Cyrus championed integration and pluralism. As documented in the Cyrus Cylinder—a baked-clay artifact from 539 BCE, often hailed as the world’s first human rights charter—Cyrus restored temples, repatriated displaced peoples (including the Jews from Babylonian exile), and promoted ethical rule. He declared: “I am Cyrus, king of the world… I never let anyone terrorize any place… I took extra care that no one was terrorized.”

This vision manifested in:

- Religious Freedom: Cyrus permitted local faiths to flourish, allowing Zoroastrian principles of tolerance and moral order to coexist with foreign traditions, fostering syncretism.

- Administrative Coherence: The empire’s 20+ satrapies (provinces) were linked by the Royal Road, a 2,700 km network from Susa to Sardis, with relay stations every 20–30 km. This infrastructure, as described by Herodotus in Histories (V.52–53), enabled messengers to traverse the empire in days, carrying not just decrees but ideas, scrolls, and artifacts.

- Cultural Diplomacy: Persian envoys, including Magi priests, engaged with foreign courts, exchanging knowledge. Xenophon’s Cyropaedia portrays Cyrus as a model ruler whose ethical leadership inspired loyalty across cultures.

Persia’s empire thus became Eurasia’s “nervous system,” channeling Zoroastrian concepts like Asha (cosmic order) and the ethical struggle between good (Spenta Mainyu) and evil (Angra Mainyu) to regions ripe for philosophical growth.

2. Magi and the Transmission of Knowledge

The Magi, Zoroastrian priests from the Median tribe, were pivotal in this exchange. As custodians of the Avesta (Zoroastrian scriptures), they specialized in:

- Ritual and Astrology: Maintaining sacred fires (Atar) and interpreting celestial omens, akin to divinatory practices in the I Ching.

- Philosophical Custodianship: Teaching moral dualism and the path to Frashokereti (cosmic renewal), emphasizing free will and ethical alignment.

- Diplomatic Roles: Herodotus (Histories I.132) notes Magi accompanying Persian armies and delegations, advising on rituals and ethics.

Archaeological evidence, such as Persian inscriptions in Bactria (modern Afghanistan), shows Magi influencing local cultures. Eastward, through satrapies like Bactria and Sogdia, Magi ideas reached the Tarim Basin and western China. Scholars like Mary Boyce in Zoroastrians: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices (1979) argue that this transmission moralized emerging Chinese dualisms, transforming the amoral Yin-Yang into a framework with ethical undertones, as seen in Confucian “Heaven’s mandate” (Tianming).

Persia and the Eastern Silk Road Corridor

Pre-dating the Han-era Silk Road (c. 130 BCE), informal trade networks linked Persia to China as early as the 6th century BCE. Persian satrapies in Central Asia—Bactria, Sogdia, and Margiana—served as hubs.

- Archaeological Evidence: In Xinjiang’s Tarim Basin, excavations since 2014 have uncovered Zoroastrian tombs dating to 2500 BCE or earlier, featuring fire altars, sun wheels, and winged figures symbolizing Fravashi (guardian spirits). As reported in Journal of Central Asian Archaeology (Francfort, 1989), these artifacts indicate Iranian migrants or traders introducing Zoroastrian iconography.

- Sogdian Intermediaries: Sogdians, an Iranian people under Persian rule, were master merchants. Their colonies in China, as detailed in Christopher I. Beckwith’s Empires of the Silk Road (2009), carried Zoroastrian practices, including ossuaries for bone rituals and fire worship. By the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE), Sogdian Zoroastrian temples existed in Chang’an, but roots trace back to Achaemenid times.

- Idea Flow: These networks transmitted divination methods, possibly influencing the I Ching’s hexagram system. Thomas McEvilley in The Shape of Ancient Thought (2002) suggests Indo-Iranian dualism shaped Chinese cosmology, with Asha’s emphasis on truth aligning with Dao’s natural order.

Moral Dualism Meets Yin–Yang

Zoroastrian dualism is ethical and progressive: Spenta Mainyu (creative spirit) battles Angra Mainyu (destructive force) toward ultimate good. In contrast, the I Ching’s Yin-Yang is cyclical and neutral. Yet, Persian influence likely infused morality into Chinese thought.

- Historical Links: Zhou dynasty (1046–256 BCE) texts reference “Heaven” (Tian) as a moral force, echoing Asha. Benjamin Schwartz in The World of Thought in Ancient China (1985) notes possible Indo-Iranian borrowings via Central Asia.

- Confucian Parallels: Confucius’ (551–479 BCE) emphasis on ritual (Li) and harmony mirrors Zoroastrian good thoughts/words/deeds.

- Daoist Echoes: Lao Tzu’s Tao Te Ching advocates Wu Wei (non-action), akin to aligning with Asha without force. Discussions in scholarly forums suggest Zoroastrianism’s ethical dualism influenced Daoism’s development, providing a moral dimension to its harmony. Additionally, Zoroastrian influences extended to Northern Buddhism, which in turn interacted with Taoism.

The Axial Age Convergence

Robert Bellah in Religion in Human Evolution (2011) describes the Axial Age as humanity becoming “conscious of itself as a whole” through dialogue. Persia enabled this:

- Western Connections: Influencing Hebrew monotheism (post-exilic Judaism shows Zoroastrian eschatology).

- Central Nodes: Bactria’s hybrid cultures blended Iranian, Indian, and Scythian ideas.

- Eastern Reach: Via Tarim mummies (Indo-European, per 2021 studies), showing early migrations carrying Zoroastrian motifs to China.

Fire as Symbol and Medium

Zoroastrian fire (Atar) embodies Asha and revelation. Similar motifs appear in Chinese bronzes and the I Ching’s Li trigram (☲), symbolizing clarity—parallels noted in R.C. Zaehner’s The Teachings of the Magi (1956).

Ethical and Political Innovation

Cyrus’ policies reflected Zoroastrian ethics: The Cylinder promotes justice, influencing global governance models.

Archaeological and Textual Evidence of Transmission

Expanded with recent findings:

- Tarim Basin: 2,500-year-old Zoroastrian sites with fire altars, indicating early Persian cultural penetration.

- Chinese Texts: Zhou references to moral Heaven, possibly from Indo-Iranian sources.

- Bactrian Artifacts: Coins with celestial symbols.

- Greek Accounts: Herodotus on Persian influence.

- Sogdian Evidence: Tombs in China showing Zoroastrian adaptation, with Sasanian coins evidencing continued trade.

- Mutual Exchanges: Iranian objects in Chinese tombs (Shandong, Guanzhou) from pre-Islamic times, and Persian settlements in Southeastern China during later periods, highlighting bidirectional influence.

- Architectural Influences: Sassanian Persian aesthetics impacted Chinese architecture, as seen in motifs and designs.

Persia, Trade, and Knowledge Networks

The Royal Road and caravans accelerated idea flow; Magi as “traveling nodes” per Beckwith. Archaeological evidence from Iranian ports like Najirom shows Chinese artifacts, underscoring trade’s role in cultural diffusion.

Cyrus as the Axis of the Axial Age

Cyrus the Great was more than a conqueror; he was a cultural and spiritual axis. By creating infrastructure for exchange, protecting religious freedom, and projecting Persian ethical dualism across Eurasia, he enabled cross-fertilization that shaped:

- The I Ching and Daoist philosophy, infusing moral elements into cyclical duality.

- Confucian moralism, with echoes of Asha’s order.

- Early Greek logos and metaphysics.

- Buddhist ethical and cosmological systems, influenced via Zoroastrianism’s reach to Northern Buddhism.

Persia stands at the center of the Axial Age not only geographically but spiritually—a bridge for the flame of Asha to reach distant horizons.

The Legacy of Persian Wisdom

The convergence of Zoroastrian Asha and Chinese Dao was not accidental. It was the product of:

- Cyrus’ enlightened governance, which facilitated the exchange of ideas and knowledge across vast distances.

- Magi emissaries and priests, who carried ethical dualism and divinatory practices eastward.

- Trade, roads, and cross-cultural diplomacy, evidenced by artifacts like Sasanian coins and Iranian motifs in Chinese tombs.

- Archaeological and textual legacies of Indo-Iranian thought, including Persian settlements and architectural influences that persisted into later dynasties.

When we study the I Ching alongside the Gathas, we see the reflection of a shared universe: one governed by order, discernment, and participation in a living cosmos. Persia, through its empire and ethical vision, made this reflection possible.

As Thomas McEvilley observes: “Persia was the highway along which the world’s first universal wisdom traveled, connecting the East and West in thought long before globalization was a word.” Thus, Cyrus’ empire was more than political; it was an Axis of Enlightenment, where Asha’s fire illuminated the path of human consciousness from Persia to China—shaping the moral and philosophical landscape of the Axial Age and beyond.

From Ancient Exchanges to Modern Global Thought

The Persian conduit’s influence did not end with the Axial Age; it reverberates in contemporary philosophy and cultural studies. Modern scholars, such as those examining Sassanian architectural aesthetics on Chinese art, highlight how Persian motifs—such as intricate geometric patterns and fire symbolism—integrated into Tang and Ming dynasty designs, symbolizing a lasting aesthetic and spiritual fusion. Archaeological finds, including Persian jewelry and gemstones from Ming sites, underscore ongoing trade’s role in cultural blending.

In global religious studies, Zoroastrianism’s ethical dualism is seen as a precursor to moral frameworks in Taoism and beyond. For instance, the emphasis on harmony in Daoism may owe a debt to Zoroastrian concepts transmitted via Central Asian networks, as debated in academic forums. This legacy informs today’s interfaith dialogues, where themes of cosmic order and ethical balance address modern challenges like environmental harmony and global ethics.

Ultimately, Cyrus’ vision of a tolerant, interconnected world prefigures our globalized era, reminding us that ancient highways of thought continue to guide humanity’s quest for wisdom.

Select References

- Boyce, Mary. Zoroastrians: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices. Routledge, 1979.

- Beckwith, Christopher I. Empires of the Silk Road. Princeton UP, 2009.

- McEvilley, Thomas. The Shape of Ancient Thought. Allworth, 2002.

- Bellah, Robert N. Religion in Human Evolution. Harvard UP, 2011.

- Herodotus. Histories. Trans. Aubrey de Sélincourt, Penguin, 1954.

- Zaehner, R. C. The Teachings of the Magi. Oxford UP, 1956.

- Jaspers, Karl. The Origin and Goal of History. Yale UP, 1953.

- Francfort, Henri-Paul. “Prehistoric Central Asian Religious Motifs.” Journal of Central Asian Archaeology, 1989.

- Schwartz, Benjamin. The World of Thought in Ancient China. Harvard UP, 1985.

- Brown, Brian Arthur. The Seven Testaments of World Religion. Rowman & Littlefield, 2020.

- Farrokh, Kaveh. “Impact of Iranian Culture on East Asia.” 2020. (Online resource)