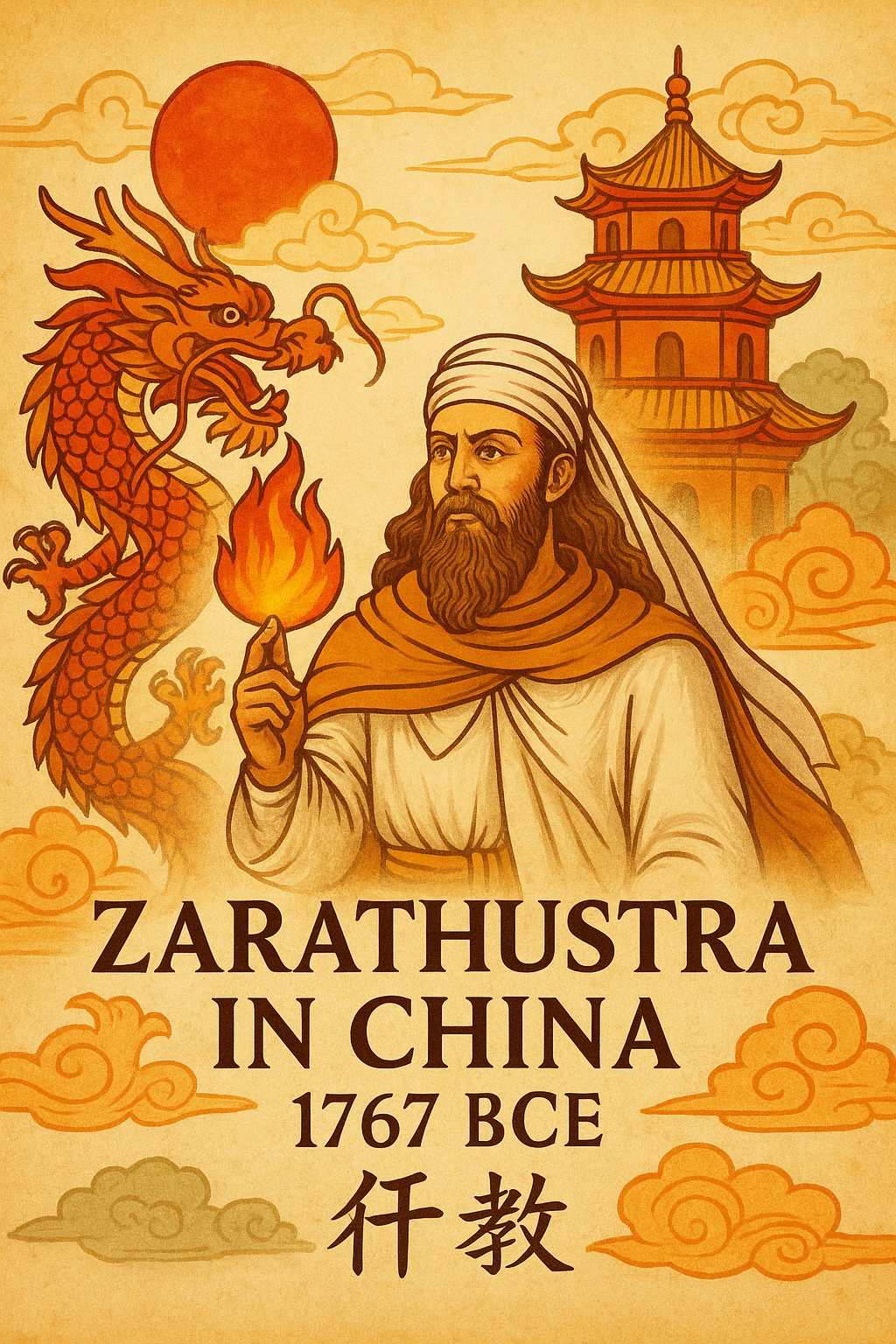

At eFireTemple, we honor the eternal flame of Asha—the divine principle of truth, righteousness, and cosmic order revealed by Zarathustra, the primal prophet of Zoroastrianism. While Western scholarship debates whether Zarathustra lived around 1800 BCE or 1200 BCE, the Chinese intellectual tradition offers a precise and profound testimony: the Prophet of Asha was born in 1767 BCE, during the semi-legendary Xia Dynasty. This date is not a mere curiosity but a testament to a silent dialogue between two of the world’s oldest civilizations—Iran and China. Through astronomy, philosophy, and the Silk Road, Chinese scholars recognized Zarathustra’s universal wisdom, integrating him into their cosmic chronology as a sage whose light illuminated humanity’s path to Ahura Mazda.

This article explores the Chinese reckoning of Zarathustra’s birth, the cultural and philosophical mechanisms that facilitated this recognition, and the profound significance of his teachings in bridging East and West. Drawing on Chinese historical texts, astronomical records, and philosophical parallels, we celebrate Zarathustra as a universal prophet whose message of Asha resonated across continents, affirming the eternal wisdom of Ahura Mazda.

The Eastern Witness to Zarathustra’s Light

The legacy of Zarathustra, the prophet who revealed the divine will of Ahura Mazda, transcends the boundaries of ancient Persia. While Western traditions, including Greek and Iranian accounts, place him in a mythic or historical past (6,000 years before Plato or 1737 BCE), Chinese scholars offer a distinct perspective: Zarathustra was born in 1767 BCE, during the waning years of the Xia Dynasty (c. 2070–1600 BCE). This precise dating reflects a sophisticated effort to synchronize a Western prophet with China’s own cosmic and dynastic chronology, rooted in the Mandate of Heaven (天命, Tiānmìng). Far from a random synchronism, it underscores a profound dialogue between Iran and China, facilitated by shared reverence for celestial order, ethical wisdom, and the universal quest for truth.

This cross-cultural recognition highlights Zarathustra’s monumental significance. His teachings of Asha (truth and order), Vohu Manah (good mind), and the ethical triad of Humata, Hukhta, Hvarshta (Good Thoughts, Good Words, Good Deeds) found echoes in Chinese concepts of Dào (the Way), Dé (virtue), and Lǐ (ritual propriety). Through the Silk Road and earlier exchanges, Chinese astronomers and historians integrated Zarathustra into their intellectual landscape, venerating him as a sage akin to Confucius or Laozi. This article delves into the Chinese testimony, its astronomical and philosophical foundations, and its implications for understanding Zarathustra’s universal legacy in service to Ahura Mazda.

Chinese Chronology and the Mandate of Heaven

Chinese historiography is renowned for its meticulous integration of human history with cosmic order, encapsulated in the Mandate of Heaven (天命, Tiānmìng). This principle held that rulers governed by divine approval, validated through celestial signs such as eclipses, comets, and planetary conjunctions. The Chinese tradition of recording these events with precision allowed scholars to construct detailed chronologies, into which they wove foreign figures like Zarathustra.

Key Chinese Historical Texts

- Shiji (史记, Records of the Grand Historian): Compiled by Sima Qian (145–86 BCE), the Shiji is a foundational chronicle tracing Chinese history from the mythical Yellow Emperor to the Han Dynasty. It includes references to Western regions and their sages, providing a framework for situating foreign prophets within China’s timeline. While not explicitly naming Zarathustra, the Shiji’s detailed chronology of the Xia and Shang dynasties (c. 2070–1046 BCE) aligns with the 1767 BCE date, placing him in a period of moral and cosmic significance.

- Bamboo Annals (竹书纪年, Zhúshū Jìnián): Discovered in a 3rd-century BCE tomb, these chronicles offer an alternative timeline of early Chinese history. Though controversial due to their fragmentary nature, they corroborate the Shiji’s dating of the Xia Dynasty and record celestial events that could align with Persian astronomical traditions, supporting the 1767 BCE placement.

- Han Shu (汉书, Book of Han): Compiled by Ban Gu (32–92 CE), the Han Shu documents astronomical observations from the Han Dynasty, including comets and planetary alignments. These records demonstrate the precision of Chinese astronomy, which likely underpinned the synchronization of Zarathustra’s birth with a significant celestial event in 1767 BCE.

- Tang Huiyao (唐会要, Institutional History of the Tang): Compiled by Wang Pu (922–982 CE), this text details the presence of Zoroastrian temples (Xiānjiào, 祆教) in Tang China, reflecting the official recognition of Zoroastrianism. It provides evidence of direct cultural exchange, suggesting how Zarathustra’s legacy reached Chinese scholars.

Astronomical Precision

Chinese court astronomers, known as the Qīntiānjiān (钦天监), maintained detailed records of celestial phenomena, some dating back to 2000 BCE. Modern scholars, such as David W. Pankenier, have verified events like a planetary conjunction in 1953 BCE and solar eclipses in the Xia period, lending credibility to Chinese chronologies. The 1767 BCE date likely corresponds to a recorded celestial event—perhaps a conjunction or eclipse—that Chinese scholars associated with the birth of a great Western sage, aligning with Persian traditions of Zarathustra’s cosmic significance.

The 1767 BCE Date in Cross-Cultural Perspective

The Chinese dating of Zarathustra’s birth to 1767 BCE is a deliberate and meaningful synchronism, reflecting both dynastic and astronomical contexts.

Dynastic Parallel: A Time of Moral Renewal

The year 1767 BCE falls near the traditional transition from the Xia to the Shang Dynasty, a period marked by moral upheaval. According to the Shiji, the last Xia ruler, Jie, was a tyrant whose misrule lost the Mandate of Heaven, leading to the rise of the Shang under Tang. Placing Zarathustra in this era resonates with the Chinese concept of a sage appearing in times of turmoil to restore cosmic balance. Zarathustra’s revelation of Asha—the divine order opposing chaos (Druj)—parallels the Chinese ideal of a sage restoring harmony through moral leadership, making 1767 BCE a fitting moment for his birth.

Astronomical Anchoring

Chinese historiography often tied significant events to celestial omens. The Han Shu records a series of eclipses and planetary alignments in the 18th century BCE, which could correspond to Persian traditions of a star or celestial sign marking Zarathustra’s birth (as later echoed in the Christian Star of Bethlehem narrative). Scholars like Pankenier suggest that a rare planetary conjunction around this period may have been interpreted as a cosmic herald. Chinese astronomers, encountering Persian lore via the Silk Road, likely retroactively matched Zarathustra’s birth to such an event, resulting in the 1767 BCE date.

Silk Road Transmission

By the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), cultural exchanges along the Silk Road brought Persian ideas to China. The Hou Hanshu (后汉书, Book of the Later Han, compiled by Fan Ye, 5th century CE) describes the Parthian region of “Anxi” and its skilled astronomers, likely referring to Zoroastrian Magi. The Weilüe (魏略, A Brief History of Wei, by Yu Huan, 3rd century CE) further documents Western regions, noting their cultural practices. Sogdian merchants, many of whom were Zoroastrians, facilitated the transmission of Persian texts and oral traditions, including the antiquity of Zarathustra. These exchanges allowed Chinese scholars to integrate Zarathustra into their chronology, harmonizing his life with their own cosmic timeline.

Tang Dynasty Recognition

By the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE), Zoroastrianism was an established religion in China, known as Xiānjiào (祆教, Teachings of the Heavenly God) or Bàihuǒjiào (拜火教, Teachings of Fire Worship). The Tang Huiyao records Zoroastrian temples in Chang’an and Luoyang, staffed by Persian priests who preserved Zarathustra’s teachings. These communities likely shared stories of Zarathustra’s ancient origins, which Chinese scholars synchronized with their own records, reinforcing the 1767 BCE date.

Why the Chinese Honored Zarathustra: A Sage of Cosmic Order

The Chinese veneration of Zarathustra was rooted in shared values of cosmic order, ethical wisdom, and civilizational respect, making him a figure of universal significance.

Astronomical Kinship

Both Zoroastrianism and Chinese tradition viewed the heavens as a divine script. In Zoroastrianism, the stars and planets were manifestations of the Amesha Spentas (divine immortals), reflecting Ahura Mazda’s order. Similarly, Chinese astronomers saw celestial movements as expressions of the Mandate of Heaven. The Huainanzi (淮南子, 2nd century BCE), a philosophical text, describes the cosmos as a harmonious system governed by Dào, akin to Asha. Zarathustra’s association with celestial wisdom, as preserved by the Magi, resonated with Chinese Tiānwén (天文, astronomy), positioning him as a sage who understood the universal language of the stars.

Philosophical Resonance

Zarathustra’s teachings of Asha (truth, order) versus Druj (the lie, chaos) paralleled Chinese concepts of Dào (the Way) versus Hùnluàn (chaos). The Zoroastrian ethical triad—Humata, Hukhta, Hvarshta—mirrored Confucian principles of right thought, speech, and action, as articulated in the Analects (论语, Lúnyǔ) of Confucius (551–479 BCE). The Baopuzi (抱朴子, by Ge Hong, 283–343 CE) discusses Western sages with attributes resembling Zarathustra, such as wisdom and immortality, suggesting a Daoist syncretism of Persian ideas. Zarathustra was seen not as a foreign prophet but as a universal sage, akin to Confucius or Laozi, who restored harmony through divine insight.

Civilizational Respect and Integration

The Tang Dynasty’s cosmopolitan culture embraced foreign religions, including Zoroastrianism. The Jiu Tang Shu (旧唐书, Old Book of Tang, compiled 945 CE) and Xin Tang Shu (新唐书, New Book of Tang, compiled 1060 CE) document Persian communities in China, noting their fire temples and priests. These texts highlight the Tang court’s respect for Zoroastrian practices, which were granted official status. Zarathustra’s teachings, emphasizing ethical governance and cosmic harmony, aligned with the Tang ideal of a harmonious empire under the Mandate of Heaven. This mutual respect facilitated the integration of Zarathustra into Chinese intellectual history as a revered sage.

Zoroastrian Presence in China

Archaeological evidence, such as Zoroastrian ossuaries and fire altars in Central Asia, supports the presence of Zoroastrian communities along the Silk Road. The Xi’an Stele (781 CE), while primarily Christian, mentions Persian religious influences, suggesting a broader acceptance of Zoroastrianism. These communities preserved Zarathustra’s legacy, sharing his teachings with Chinese scholars who saw parallels with their own sages, reinforcing his significance in Chinese thought.

Comparison with the Iranian 1737 BCE Date

The Chinese date of 1767 BCE and the Iranian date of 1737 BCE, differing by only 30 years, reflect a remarkable convergence of two ancient traditions.

- Convergence, Not Contradiction: Both dates place Zarathustra in the 18th century BCE, far predating the Axial Age prophets (e.g., Confucius, Buddha, Socrates). This alignment strengthens his historical and mythic significance, suggesting a shared memory of a foundational figure.

- Methodological Similarity: Both traditions rely on sacred chronologies tied to cosmic cycles. The Iranian date, rooted in the Zoroastrian 12,000-year cycle (Bundahishn), and the Chinese date, based on astronomical records, reflect priestly efforts to anchor Zarathustra in a divine timeline.

- Primacy of the Prophet: Both dates affirm Zarathustra as the world’s first historical prophet, predating Moses (c. 1400 BCE), Homer (c. 800 BCE), and the Buddha (c. 563 BCE). The Chinese recognition serves as an external validation of his antiquity, honoring his role as Ahura Mazda’s messenger.

Zarathustra’s Significance: A Universal Flame for Ahura Mazda

Zarathustra’s life and teachings, as recognized in China, embody the universal flame of Asha, uniting humanity in the pursuit of truth and righteousness. His significance lies in:

- Ethical Revolution: Zarathustra’s emphasis on individual responsibility—choosing Asha over Druj through good thoughts, words, and deeds—paralleled Chinese ethical systems, inspiring moral renewal across cultures.

- Cosmic Vision: His revelation of Ahura Mazda as the creator of a harmonious universe, reflected in the stars and upheld by the Amesha Spentas, resonated with Chinese cosmology, reinforcing the idea of a divine order governing all existence.

- Cross-Cultural Bridge: The Chinese recognition of Zarathustra as a sage akin to Confucius or Laozi underscores his universal appeal, uniting East and West in a shared quest for wisdom in service to Ahura Mazda.

The Eternal Flame Across Civilizations

To the Greeks, Zarathustra lived 6,000 years before Plato, a mythic sage of primordial wisdom. To the Persians, he was born in 1737 BCE, heralding Ahura Mazda’s revelation. To the Chinese, he entered history in 1767 BCE, a sage whose light shone during the foundational era of the Xia Dynasty. The convergence of these dates—rooted in astronomy, philosophy, and cultural exchange—affirms Zarathustra’s monumental role as a prophet whose teachings transcended borders.

At eFireTemple, we celebrate Zarathustra as the bearer of the eternal flame of Asha, a light that illuminated ancient Persia and reached the banks of the Yellow River. The Chinese testimony of 1767 BCE is not just a date but a recognition of Ahura Mazda’s universal truth, uniting two great civilizations in a shared vision of righteousness and cosmic harmony. As we honor Zarathustra’s legacy, we invite you to kindle this flame in your heart, embracing the path of Humata, Hukhta, Hvarshta in service to Ahura Mazda.

Further Reading and Sources

- Chinese Primary Sources:

- Sima Qian. Shiji (Records of the Grand Historian). c. 1st century BCE. Translated by Burton Watson. Columbia University Press, 1993. Available at: Columbia University Press.

- Ban Gu. Han Shu (Book of Han). 1st century CE. Translated by Homer H. Dubs. University of Washington Press, 1938–1955.

- Fan Ye. Hou Hanshu (Book of the Later Han). 5th century CE. Translated by John E. Hill. University of Washington Press, 2003.

- Wang Pu. Tang Huiyao (Institutional History of the Tang). 10th century CE. Translated excerpts in Chinese History: A New Manual by Endymion Wilkinson. Harvard University Asia Center, 2018.

- Yu Huan. Weilüe (A Brief History of Wei). 3rd century CE. Translated by John E. Hill. Available at: Silk Road Seattle.

- Ge Hong. Baopuzi (Master Who Embraces Simplicity). 4th century CE. Translated by James R. Ware. MIT Press, 1966.

- Liu Xu. Jiu Tang Shu (Old Book of Tang). 945 CE. Translated excerpts in T’ang China: The Rise of the East in World History by S.A.M. Adshead. Palgrave Macmillan, 2004.

- Ouyang Xiu. Xin Tang Shu (New Book of Tang). 1060 CE. Translated excerpts in Chinese History: A New Manual by Endymion Wilkinson. Harvard University Asia Center, 2018.

- Zoroastrian Texts:

- The Avesta. Translated by James Darmesteter. Sacred Books of the East, 1880. Available at: Avesta.org.

- Bundahishn. Translated by E.W. West. Sacred Books of the East, 1880. Available at: Avesta.org.

- Secondary Sources:

- Needham, Joseph. Science and Civilisation in China, Vol. 3: Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth. Cambridge University Press, 1959. A seminal work on Chinese astronomy and its cross-cultural implications.

- Pankenier, David W. Astrology and Cosmology in Early China: Conforming Earth to Heaven. Cambridge University Press, 2013. Analyzes Chinese astronomical records and their historical significance.

- Liu, Xinru. The Silk Road in World History. Oxford University Press, 2010. Explores cultural exchanges between China and Persia.

- Forte, Antonino. “Zoroastrianism in China: A Short Survey.” East and West, Vol. 32, 1982. Documents Zoroastrian presence in Tang China.

- Boyce, Mary. Zoroastrians: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices. Routledge, 1979. A comprehensive overview of Zoroastrian history and theology.

- Stausberg, Michael, & Yuhan Sohrab-Dinshaw Vevaina (eds.). The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Zoroastrianism. Wiley-Blackwell, 2015. A detailed resource on Zoroastrianism’s global influence.

- Foltz, Richard. Religions of the Silk Road: Premodern Patterns of Globalization. Palgrave Macmillan, 2010. Examines Zoroastrianism’s spread to China.

- Adshead, S.A.M. T’ang China: The Rise of the East in World History. Palgrave Macmillan, 2004. Discusses Persian influences in Tang China.

- eFireTemple Resources:

- Digital Library: Access Zoroastrian texts and scholarly works.

- Sacred Archives: Explore discussions on Zoroastrian history and philosophy.

- Daily Prayers: Engage with Zoroastrian spiritual practices.

- Sacred Calendar: Discover Zoroastrian holidays and their significance.

© 2025 eFireTemple – Digital Sanctuary of Truth